Genre, Manifolds, and AI.

This article in the New Yorker about the end of genre prompts me to share a theory I’ve had for a year or so that models at Spotify, Netflix, etc, are most likely not just removing artificial silos that old media companies imposed on us, but actively destroying genre without much pushback. I’m curious what you think.

This aligns to the most important rule for thinking about artificial intelligence, which is that it’s deleterious effects are most likely in places where decision makers are perfectly happy to let changes in algorithms drive changes in society. Racial discrimination is the most obvious field where this happens. But there are others where the moral valence is less clear, which are mostly being ignored.

Background: I’m participating in a [roundtable at the American Historical Association tomorrow](https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WNzaX-6GpgTTaQEveJ8BulOQ) on Artificial Intelligence and its implications for the future of historical research. It made me realize that while I’ve been fiddling quite a bit with neural networks, and used them in my article on dimensionality reducation in digital libraries, I haven’t actually reflected much on them. Some of that will hopefully appear in the published partner to the AHA panel._

I teach a course on the history of data, and one primary lesson is that indexes shape what kind of culture people use. So with modern culture, what kind of indices do we use? When I did college radio,, in the music library the most important resource was a set of huge printed binders for every piece in the station’s music library printed out twenty years before; there were different binders by artist, by composer, etc. But by far the most useful one was a listing of every track in the collection by time; you’d know you needed an instrumental piece that was between 18 and 19 minutes long to close out a shift, and you could retrieve it instantly. How things were stored affected what got played.

The promise of digitization is unconstrained reconfiguration; indexes like this shouldn’t matter anymore. But of course we still have indexes, and I wonder if they aren’t doing something quite weird.

Unevenly distributed high-dimensional spaces privilege non-conformism

The theory is this. If you assume that music is distributed in a high-dimensional feature space (as they surely do) the distribution of pieces in that space is almost sure to be highly uneven. Some areas (recordings of the Beethoven string quartets) will be densely populated; others (suites for toy piano) will be quite sparse.

If you then use k-nearest neighbors approaches to serve up recommendations for music (Spotify built the best-known library, so we know that they use it), you’ll likely hit music on the periphery of its local clusters far more often than music at the center.

Here’s a simple 2-d analogy. Imagine an alien crashing into a random point on Earth and searching for the nearest human to say “take me to your leader.” The odds are they’ll find someone rural; and it’s basically guaranteed they’ll hit a suburbanite before an urbanite unless they happen to crash into the middle of Central Park. They’re more likely to meet a Russian speaker than a Chinese speaker. And so on.

Spotify isn’t serving up songs randomly, but I wonder how much a similar dynamic comes into play when each person is turned into a vector to predict their next streams.

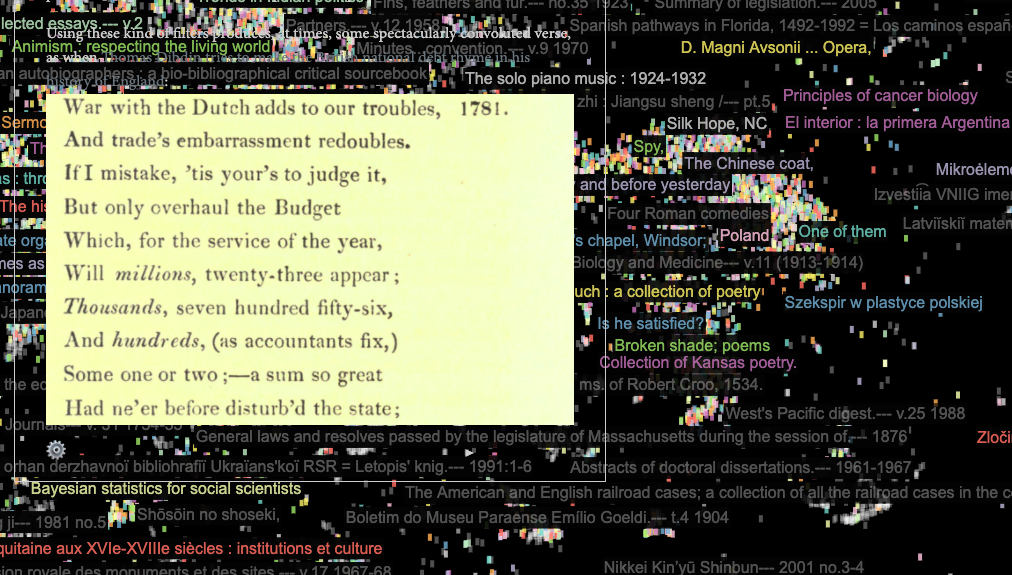

When I browse around this vector representation of all the books in the Hathi Trust I made, genre outliers just tend to pop out naturally. I love these, because they’re intrinsically interesting; I end up finding– for instance–a book telling the history of England in doggerel just as often as I find “normal” poetry.

A doggerel poem from an 18th century book.

For those of who can’t read it:

And trade’s embarrassment redoubles.

If I mistake, ^tis your’s to judge it,

But only overhaul the Budget

Which, for the service of the year,

Will millions, twenty-three appear ;

Thousands^ seven hundred fifty-six,

And hundreds, (as accountants fix,)

Some one or two ; a sum so great

Had ne’er before disturb’d the state;

But I’ll certainly get the wrong idea about what sort of books exist in the library if I assume that the elements that pop out in the less dense areas are more typical. In fact, I’d probably To some degree, Spotify is doing the same thing with music. And instead of cities and rural people, we have dense established genres.

What is Spotify recommending?

My thinking about this has been heavily influenced by thinking about what I listen to now that I mostly use Spotify rather than my own digitized CDs for music listening. A typical example that Spotify’s recommendation algorithm surfaced for me quite early on is the music of the Austrian theorbist and composer Christina Pluhar, who puts together ensembles which, depending on your taste, are enchanting, insufferable, or inane. Here’s a track from her album of Purcell arrangements.

I like this. I have no idea idea if you do; and I don’t know exactly why I was recommended it. But if you assume this came out of a nearest-neighbor search in some region of a high-dimensional space, it’s easy to imagine why. This is an album that sits at an intersection of a bunch of different styles; recklessly loose early-music bands, non-traditional world music borrowers, Leonard Cohen “Allelulia” completists. Not something for everyone; but something for several different groups that ensures it will float way off in its own region of an embedding space.

What doesn’t Spotify surface? That’s a much harder question to answer. But I know that the only album I’ve recommended to anyone recently probably fits the bill quite nicely; the last couple disks of the Beaux-Arts Trio’s complete Haydn Piano Trios.

Without streaming, this is probably a less obscure disk than the Pluhar, but it’s also pretty damned obscure in its own right. The Haydn trios are far less often played than his string quartets or symphonies because those two genres ended up becoming more prestigious, but Haydn didn’t know that, and the music is equally as good. And while late Haydn has its own deeply appealing weirdness, I find it hard to imagine that there are any existing listeners out there who come to it before mostly exhausting their path through the Beethoven piano sonatas and Mozart quartets first. Pluhar’s music is sitting in a cabin in the Canadian woods waiting for any comers; Haydn’s trios are crammed into several walkups in Ditmars Steinway along with C.P.E. Bach, Boccherini, the rest of the less-trafficked classical canon.

Is genre disappearing everywhere?

So is this happening everywhere in culture? The degree to which its an algorithmic product isn’t clear, but it sure seems like the streaming services have settled into a bubble of half-hour unclassifiable formats rather than “sitcoms” and “dramas.” Netflix’s “personalized genres” are not the product of an embedding system, but do play naturally alongside one, because they generate an affinity for works that cut across different realms.

The causation here is complicated because, as with many other trends, the technology merely gloms onto a larger cultural trend. It seems quite possible to me that music recommendation services succeed right now because the zeitgeist is aligned in a way where many people are amenable to being served these kinds of hybrid works. If you want pure genre, there are ways of getting it; modern satellite radio stations, like Sirius-XM, will give you all the expert-curated music you want for any microgenre imaginable.

Is this a problem? I don’t think many would see it as such; but it’s worth thinking, nonetheless, about what it does to culture. Anyone who manages to occupy an empty space in the cultural manifolds will be richly rewarded; anyone who tries to stay in a heavily-trafficked space will languish. The idea of cultural areas as fluid, non-differentiable groups flowing into each other will be a self-fulfilling prophecy; anyone insisting that genres are real may seem hopelessly old fashioned. Anyone who navigates cultural spaces through digital means will be over-exposed to hybrid cultural forms, which will only lead them further to think that the different genres were an old-fashioned illusion, brought about by a particular set of constraints around channels, record labels, and the rest. And of course they’ll be right. But if they think there’s anything more natural about an enforced space emphasizing novelty, sparsity, and so forth, they’ll be wrong; and a cultural dynamic around filling in the valleys of a manifold spaces rather than building up the summits may be less rewarding than we hope.